McDermott+ is pleased to bring you Regs & Eggs, a weekly Regulatory Affairs blog by Jeffrey Davis. Click here to subscribe to future blog posts.

November 20, 2025 – We are still waiting for the Centers for Medicare & Medicaid Services (CMS) to issue the remaining three calendar year (CY) 2026 Medicare payment rules. While the official deadline for releasing all four CY 2026 rules was November 1, 2025, CMS only made the deadline for one, the Physician Fee Schedule (PFS) final rule, which was released on Halloween. Stakeholders have been waiting with bated breath for the other three:

Regs & Eggs will explore the OPPS rule once it’s released. In the meantime, we wanted to do another deep dive into the PFS rule. Embedded in the 2,300+ page rule is a new CMS Innovation Center payment model, the Ambulatory Specialty Model (ASM). After CMS initially proposed the model, my colleague Simeon Niles and I highlighted the model’s core features in this post. I’m delighted to bring Simeon back in to discuss some of the public comments that CMS received on the ASM and how the final model compares to CMS’s initial proposal.

The ASM is based on the Merit-based Incentive Payment System (MIPS) Value Pathways (MVP) program. MIPS is the main quality reporting for clinicians under Medicare, and MVPs represent a streamlined reporting option that enables MIPS-participating clinicians to choose from a narrow set of measures based on a specialty, episode, or condition.

CMS finalized nearly all elements of ASM as proposed, essentially turning two sets of MVPs into a new alternative payment model (APM) and signaling that this model is intended to be a major structural shift in how Medicare holds specialists accountable for outcomes, cost, and care coordination in high-spend chronic conditions. During the public comment period on the proposed rule, some commenters expressed concerns about using the MVP framework as the basis for the model, as MVPs are a relatively new reporting pathway and participation thus far has been limited. They encouraged CMS to wait until more robust participation data is available for MVPs before it designs a whole APM based on this framework. CMS acknowledged these concerns but emphasized the advantages of mandating MVPs, including use of narrower measure sets aligned with specific specialties and conditions.

The ASM is a five-year model that will require physicians in select geographic regions who meet the specialty and episode volume criteria (i.e., a 20-case minimum) to report modified versions of MVPs for heart failure and low back pain with altered performance and scoring rules from MIPS. CMS finalized two specialist cohorts:

Most of these specialties currently participate in MIPS and are not involved in an APM. Some commenters requested that CMS include other clinicians (e.g., physical therapists, chiropractors, and non-physician practitioners), but the agency declined, citing limitations in Medicare specialty codes and concerns about comparability. Unlike MIPS, which allows for performance assessment at the group or APM entity level, ASM will evaluate each clinician independently (i.e., at the TIN/NPI level) to “level the playing field,” particularly for small and solo practices. The model will begin in 2027 and end in 2031. Like MIPS, bonuses and penalties will be applied two years after the performance period, so the last set of financial adjustments will occur in 2033.

The ASM will maintain the four MIPS performance categories (quality, cost, improvement activities, and promoting interoperability). However, CMS finalized performance category weights that differ from MIPS. CMS will apply a 50/50 weighting of quality and cost, with only negative adjustments possible for promoting interoperability and improvement activities. This confirms that promoting interoperability and improvement activities cannot increase a clinician’s score, only decrease it if requirements aren’t met.

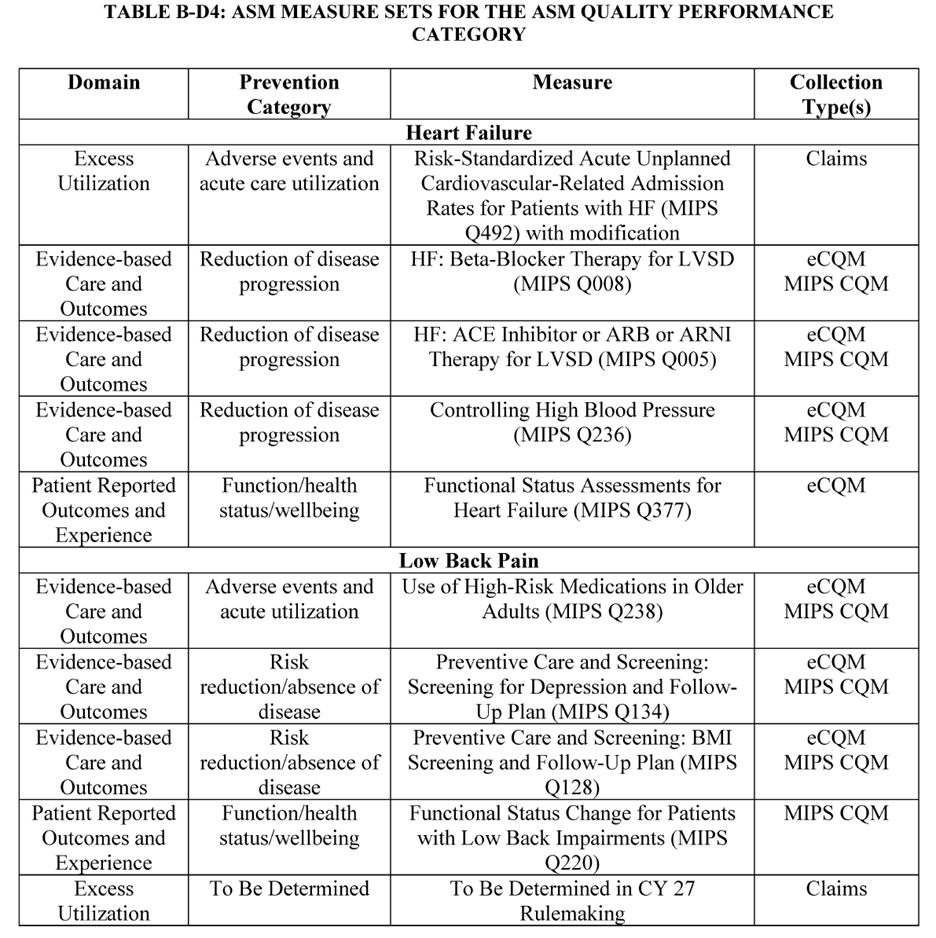

Unlike MIPS, clinicians will not be able to choose their own measures. Instead, they will be required to report on a set of prespecified measures tailored to their specialty and condition (see Table B-D4 from the final rule). CMS originally proposed to include a respecified magnetic resonance imaging lumbar spine for low back pain measure in the low back pain quality measure set, but did not finalize that proposal because the measure was still in development. The agency intends to revisit the measure or alternatives in the CY 2027 rule.

One of the most controversial aspects of ASM is its reliance on a relative scoring methodology to determine quality performance. CMS finalized that quality will be scored in equal deciles among peers in each cohort. This means that clinicians will not be graded relative to a national absolute benchmark, but instead will be assessed relative to one another. Some commenters stated that a decile-based approach fails to recognize both attainment and improvement, since it guarantees that a portion of providers will fall into the lowest tiers even if overall quality rises. CMS disagreed, stating that peer-relative scoring is effective at rewarding high performers while encouraging those who are below the cohort average to improve. The cost performance category will use the MIPS episode-based cost measure methodology, which relies on “around the median” distributions that function more like a curve. Clinicians’ cost performance will be determined relative to a cohort-specific median with ranges based on standard deviations.

CMS will make positive, neutral, or negative adjustments to clinicians’ Medicare Part B payments to ensure budget neutrality, as in MIPS. Clinicians’ Part B payments at risk under the model start at 9% beginning in the 2027 performance year/2029 payment year and grow to 12% by the 2031 performance year/2033 payment year. CMS will retain 15% of total funding at risk. In other words, while MIPS (and therefore MVPs) is a budget-neutral program (i.e., all penalties are used to pay bonuses), this APM is designed to guarantee savings for the Medicare program.

Alongside the major ASM payment and accountability changes finalized in the CY 2026 PFS final rule, CMS included several flexibilities designed to make the model easier for clinicians to deliver care to patients living with heart failure and chronic low back pain. Two of the most important flexibilities relate to beneficiary incentives and telehealth.

For the first time in a specialty-focused Medicare model, CMS will allow participating clinicians to offer up to $1,000 per beneficiary in in-kind patient engagement incentives that help patients stay engaged in their care. For example, these incentives can support participation in education or coaching programs, use of remote monitoring tools (e.g., blood pressure monitors), vouchers for healthy food, or gym memberships. This is made possible through a waiver of fraud and abuse laws (e.g., certain Anti-Kickback Statute provisions) that would otherwise prohibit incentives that might be viewed as inducing beneficiaries to seek care from a particular provider. This is an important signal that CMS wants to encourage patients to take a more active role in managing their chronic conditions, not just show up for appointments. However, there is one wrinkle: the rule is not clear on whether the $1,000 cap applies per year or over the patient’s lifetime. As written, it could be interpreted as a lifetime cap, which would restrict how incentives can be used for patients who need long-term support. Use of incentives also comes with significant documentation requirements, and CMS did not provide additional funding to help practices pay for the incentive itself. For many specialists, particularly small and solo practices, these barriers may limit uptake. Still, many stakeholders have commented that the flexibility is a positive step toward more patient-centered care.

CMS also finalized a set of telehealth flexibilities that allow specialists in ASM to see patients virtually without being restricted by traditional Medicare telehealth rules. CMS plans to waive the geographic and originating site requirements to allow ASM beneficiaries to receive telehealth services in their homes. This flexibility is especially valuable in chronic condition management, where patients need frequent follow-ups that can be done virtually.

CMS plans to announce preliminarily eligible ASM participants by the end of 2025 and release a final list in July 2026 for the 2027 performance year/2029 payment year.

Because the ASM does not start until January 1, 2027, stakeholders could have additional opportunities down the line to provide input. CMS’s decisions regarding this model could signal how CMS plans to get more specialists, who up until now have had limited opportunities to participate in APMs, to transition to APMs going forward.

Regs & Eggs will be on hiatus next week for the Thanksgiving holiday. Until December 4, this is Jeffrey (and Simeon) saying, enjoy reading regs with your eggs.

For more information, please contact Jeffrey Davis. To subscribe to Regs & Eggs, please CLICK HERE.